Father George Daly, Redemptorist director of the Sisters of Service, and the Sisters at their First Chapter to discuss the issues of the institute, Toronto, May 1937. Sister Catherine Donnelly is in the middle row, third from the left. (SOSA 9-03.1-3-14, The Field at Home-July 1937)

In the boardroom of the Sisters of Service headquarters in Toronto, four photographic portraits hang prominently on the north wall. These photos are of the foundress and the three priests who were instrumental in the establishment and the early vision of this women’s missionary community in Canada.

On the wall, the central photo is of Catherine Donnelly, the foundress of the Sisters of Service, who originated the idea of an institute of women religious serving in Western Canadian settlements.

Two Redemptorists are placed together: Rev. Arthur Coughlan, Provincial Superior of the Toronto Province who with Catherine Donnelly initiated the founding, and Rev. George Daly, who directed and supervised the development of the Sisters of Service for 34 years. The other photo is of Archbishop Neil McNeil of Toronto, who guided the early canonical establishment of the institute.

This article proposes to examine the influence and the later connection of the Toronto Province of Redemptorists in the development of the Sisters of Service with particular focus on Fr. Daly’s direction from 1922 until his death in 1956.

The idea of the Sisters of Service originated with Catherine Donnelly as a result of her experiences in Western Canada at the end of the First World.1

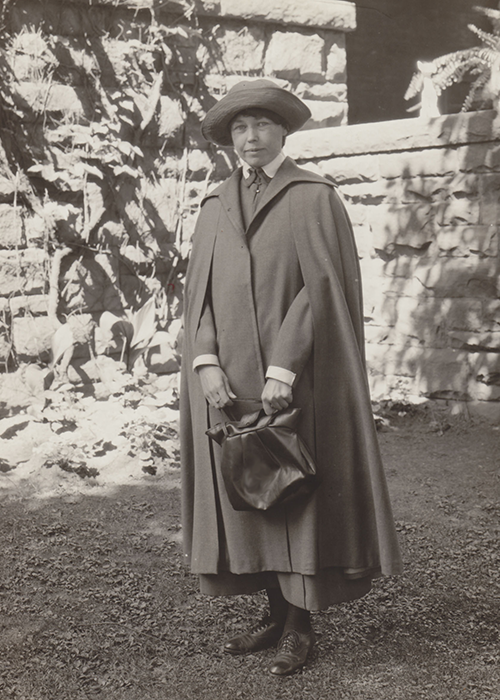

Catherine Donnelly, Alliston, Ontario, 1914.

(SOSA 9-01.4-2-1)

Catherine Donnelly was born in 1884 on a farm 50 miles north of Toronto. Her parents were Irish immigrants, and she grew up in a community of Irish Protestant and Catholic settlers, who had come to the central Canadian province of Ontario after the potato famine in Ireland.

The eldest of three daughters, Catherine Donnelly earned a teaching certificate in 1902 and taught in one-room schoolhouses in Ontario. After the death of her mother in 1905, Catherine Donnelly, then 21, became the sole financial support for her two teenage sisters and her father, who had sold the heavily-mortgaged farm. For almost 12 years, Catherine Donnelly taught in a series of public schools in rural and central Ontario, moving frequently to seek a higher salary and became one of the highest-paid teachers in Ontario at $925 a year.2

By the late summer of 1918, family obligations had lessened, Catherine Donnelly and a fellow teacher travelled to the Canadian West in a spirit of adventure.3

The previous year, 1917, Canada with a population of eight million had celebrated 50 years as a country.4 A railway crossed the vast land from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific. In 1905, the two prairie provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were established, partially with the intention that the settlement of their expansive arable land could fill the Eastern Canadian desire for new markets of their manufactured goods in exchange for prairie wheat.5

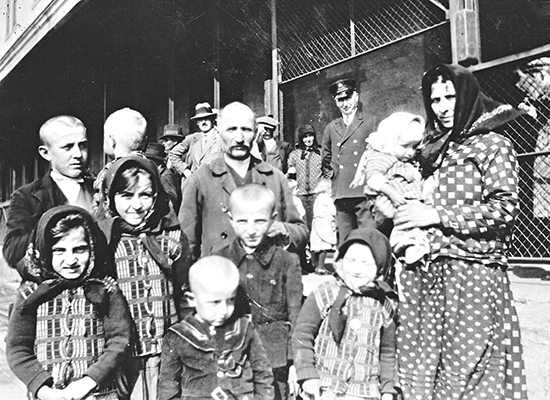

Recently-arrived family outside the Immigration Building, early 1930s. (SOSA 9-06.17.3-20-6)

Just before the turn of the 20th century, the Canadian government accelerated its immigration search and opened these prairie lands to East European and Slavic immigrants beyond the previous settlers from the British Isles and Western Europe. Under the Dominion Lands Act of 1872, which only applied to the prairies, a homesteader would receive160 acres for $10. The act also called for a house, often of log or sod, to be built and a specified area of land to be cultivated within three years.6

This policy of almost free land grants was successful in attracting an influx of immigrants from Eastern Europe. In a 15-year period, more than a million homesteaders took advantage of the free land in the prairie provinces. In the central prairie province of Saskatchewan, the population jumped to 650,000 in 1916 from 91,000 in 1901.7

Despite the cheap land, life was difficult. Homesteaders and their families were often separated from their friends and relatives. Many suffered years of hardship and loneliness with the absence of roads and bridges.8

Catherine Donnelly and her friend discovered firsthand the lack of services and infrastructure in these newly-established communities. They taught in two small one-room schoolhouses near Stettler, in the heart of Central Alberta, for six weeks before the dreaded Spanish influenza, brought by the returning soldiers from Europe, spread throughout the district. By mid-November, the schools were closed. The two teachers served as volunteer nurses and undertook home nursing duties.9

What struck them as they helped these families was the absence of recognition of any spiritual help. They had found that many Catholics, the majority of them Eastern European, especially of the Ruthenian Rite, no longer practised their religion. Catherine Donnelly observed:

“Their Catholic faith is the one treasure these newcomers have brought from the Old Land and heresy, schism and atheism are working hard to rob them of it. … Who is there going to ensure that they retain their treasure? Not the priests, who are so few, not lay teachers, not any order of nuns working at present.”10

The Church’s indifference to the spiritual and educational needs of the rural areas of the West deeply distressed her. She was certain that this would result in irreparable harm to these abandoned souls and also damage the Church’s reputation. With this constant reminder, she came to the conclusion that a teaching order of Sisters would be the solution, but she felt that none of the religious communities working in the West was suitable.11

In November 1919, she returned home to the deathbed of her father, who died a few weeks later. Early in the next year, Catherine sought an interview with Fr. Coughlan. Her sister Mamie, then a novice with the Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto, had recommended him. Fr. Coughlan had gained a reputation for kindly and practical advice on spiritual matters and as a popular retreat master and confessor to several religious orders.12

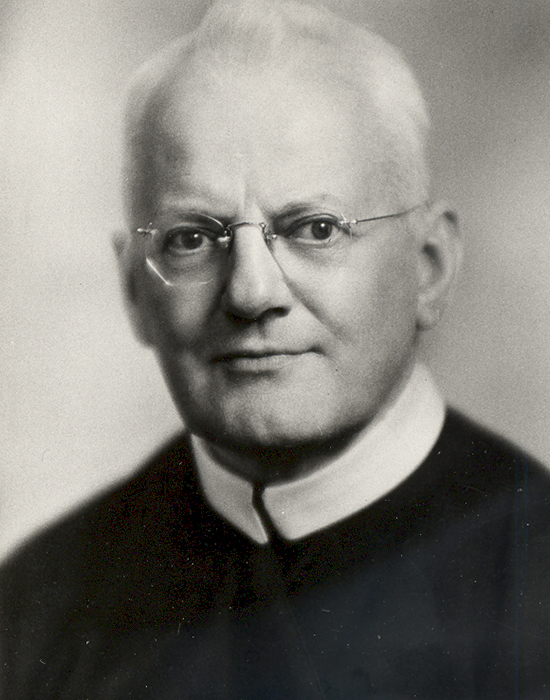

Father Arthur Coughlan, C.Ss.R.

(SOSA 9-02.2-0B2)

A member of the Baltimore Province, Fr. Coughlan had come to Toronto in 1913 to fill a request from Toronto Archbishop McNeil, who wanted the Redemptorists to work among the Italian immigrants in Toronto. For two years, Fr. Coughlan, who spoke Italian, had performed well in this appointment - so much so that in 1915, he was appointed as rector of St. Patrick’s Church, the Redemptorists flourishing downtown Toronto parish and as secretary consultor to the Vice Provincial Rev. Patrick Mulhall.13

When Catherine Donnelly came to see Fr. Coughlan, the Toronto Province had been founded two years previously with nine foundations with mission bands14 attached to most of them. The Province consisted of five large city parishes in Eastern Canada: Saint John in New Brunswick; Quebec City, Montréal in Québec,Toronto and London, Ontario, and the four small parishes in Western Canada: Yorkton and Regina in Saskatchewan; Brandon and East Kildonan (Winnipeg) in Manitoba.15

As secretary consultor of the Toronto Vice Province and Toronto Province, Fr. Coughlan was aware of the problems of the booming West from the confreres posted there and understood Catherine Donnelly’s concern about the “abandoned” rural families in Western Canada. He was impressed with her plan of teaching Sisters in rural communities. However, he suggested that Catherine Donnelly join an established order and persuade them to expand into this promising field of religious and secular education.16

Her two attempts of joining the Sisters of St. Joseph met with disappointment. She was refused acceptance to one community and left as a postulant after three months from another. Just before Christmas in 1920, Catherine Donnelly reported her lack of success to Fr. Coughlan, now the Toronto Provincial Superior17, who remarked: “‘You probably spoke too much about the West.’ Suddenly he threw his head back and laughed heartily, suggesting, ‘You had better start a community of your own.’”18

During the next 18 months, the two consulted and consolidated the details of the new community along with Archbishop McNeil, who extended his support. Both clerics accepted Catherine Donnelly’s choice of the name as the “Sisters of Service,” and agreed the Sisters would teach in the rural settlements in western Canada. Breaking free from the semi-cloistered monastic restrictions, the Sisters would live among the people they were serving, would dress in a simple uniform, would keep their Christian and surnames and observe a modified daily regimen.19

However, Fr. Coughlan was immersed in the Provincial administration of launching a juvenate and Novitiate and expanding the Toronto Province further into Western Canada.20 He decided to delegate some responsibility for the Sisters of Service and appointed Fr. Daly to assist in establishing the institute. Within a month, Fr. Daly arrived at St. Patrick’s monastery, the provincial headquarters, where he would live for the rest of his life.21

Father George Daly, C.Ss.R., 1948.

(SOSA 9-01.3-9-14)

Fr. Daly was a native of Montréal, whose family were parishioners of the Belgian Redemptorist parish of St. Ann’s. At the age of 16, he entered the Redemptorists novitiate in St. Trond, Belgium, where he was ordained in 1899. Returning to Canada in 1900, he was a rising star with much potential as a Canadian fluent in both English and French. During the next 12 years at the minor seminary at St.-Anne-de-Beaupre, he was appointed to a series of positions as socius,22 prefect of students and finally, seminary director. In 1912, he returned to his home parish of St. Ann’s in Montréal as its first rector under the new Vice Province of Toronto.23

As part of the English-Canadian Redemptorist expansion into Western Canada, he was sent in 1915 as rector of the newly-built Holy Rosary Cathedral in Regina, Saskatchewan. In this farthest west of the Redemptorist Canadian foundations, Fr. Daly used every minute to learn and travel about the booming area, which was dominated by the Protestant and English culture. He gave retreats in the poorest areas and established the Catholic Truth Society in Saskatchewan. However, it was his free-wheeling ways, use of modern technology of telephones and automobiles, friendships with politicians and bishops as well as his public appearances for the war effort which caused his superiors to conclude that Fr. Daly did not have the proper humility and adherence to poverty.24

He was removed abruptly in 1918 to Saint John, New Brunswick as a missionary. Despite the change in assignment, he remained interested and concerned about the plight of immigrants and isolated settlers, meeting the immigrant boats at the city’s harbour and corresponding with Mother Mary McKillop’s missionaries in the outback of Australia.25 During this time, he also wrote Catholic Problems in Western Canada, a book as a result of his appointment in Regina. In it, he outlined plans for the Canadian Church’s expansion in the West.26

Archbishop McNeil of Toronto shared Fr. Daly’s analysis in the book and concern of the Church’s response to newly-arrived immigrants. Critical of “our lack of success in the past … due to insufficient effort,” the archbishop described the founding of the Sisters of Service as “a very important step towards a solution of the problem of immigration, safeguarding of the faith with social and civic betterment.”27

Foreseeing the Sisters of Service as a non-monastic community, wearing uniforms, not habits, and travelling in pairs into lonely settlements, Fr. Coughlan was clear on the priorities: “What we need now is money and candidates.”28

These two tasks were assigned to Fr. Daly, who was in his prime at 50 years old and his “dark days had passed.”29 With a beaming smile, outstretched hand, boundless energy, an apostle’s determination along with an executive’s organizational skill, Fr. Daly possessed the entrepreneurial spirit and engaging personality needed to raise funds and attract candidates to the fledgling community.30

In a whirlwind of speaking engagements, he made new contacts and renewed others with Catholic organizations like the Truth Societies, the Catholic Women’s League as well as with influential and well-connected friends and financial backers. A number of the pioneer Sisters became interested in the community after attending one of Fr. Daly’s talks. He wrote to each of the Bishops in Western Canada, enclosing a booklet he had written about the new community as a point of information for donations and invitations to come and work in their dioceses.31

The Rule of the Institute of the Sisters of Service, also drafted by Fr. Daly, was based primarily on the previous agreements of Catherine Donnelly, the archbishop and Fr. Coughlan and on the theology and spirituality of St. Alphonsus “to serve the most abandoned.”32

The writings and spiritual teachings of St. Alphonsus formed the basis of the Novitiate training: The True Spouse of Jesus Christ, The Glories of Mary and The Way of Salvation and Perfection were the basic texts.33 Patron Saints of the institute included Our Mother of Perpetual Help, St. Joseph, St. Alphonsus and St. Theresa. Like the Redemptorists, the characteristic virtues of the Sisters of Service were charity, humility, mortification and zeal.34

Other Redemptorist practices, including the Virtue for the Month, visits to the Blessed Sacrament and the rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary were part of the community spirituality. A reproduction of the icon of Mother of Perpetual Help hung in each mission at the centre of a shrine. Fr. Coughlan, who was the spiritual director for the first five years, introduced the custom of the coronation of Our Lady in the month of May, which was continued when Fr. Daly succeeded him as spiritual director.35

With a sense of urgency, Fr. Daly began putting into reality the ideals of the Rule. The Redemptorist mission clearly can be seen as the Sisters of Service “were to possess the zeal for the salvation of the most abandoned souls in the outlying districts of our new Provinces. This zeal will manifest itself particularly in dealing with the poor, the ignorant and the most abandoned.”36

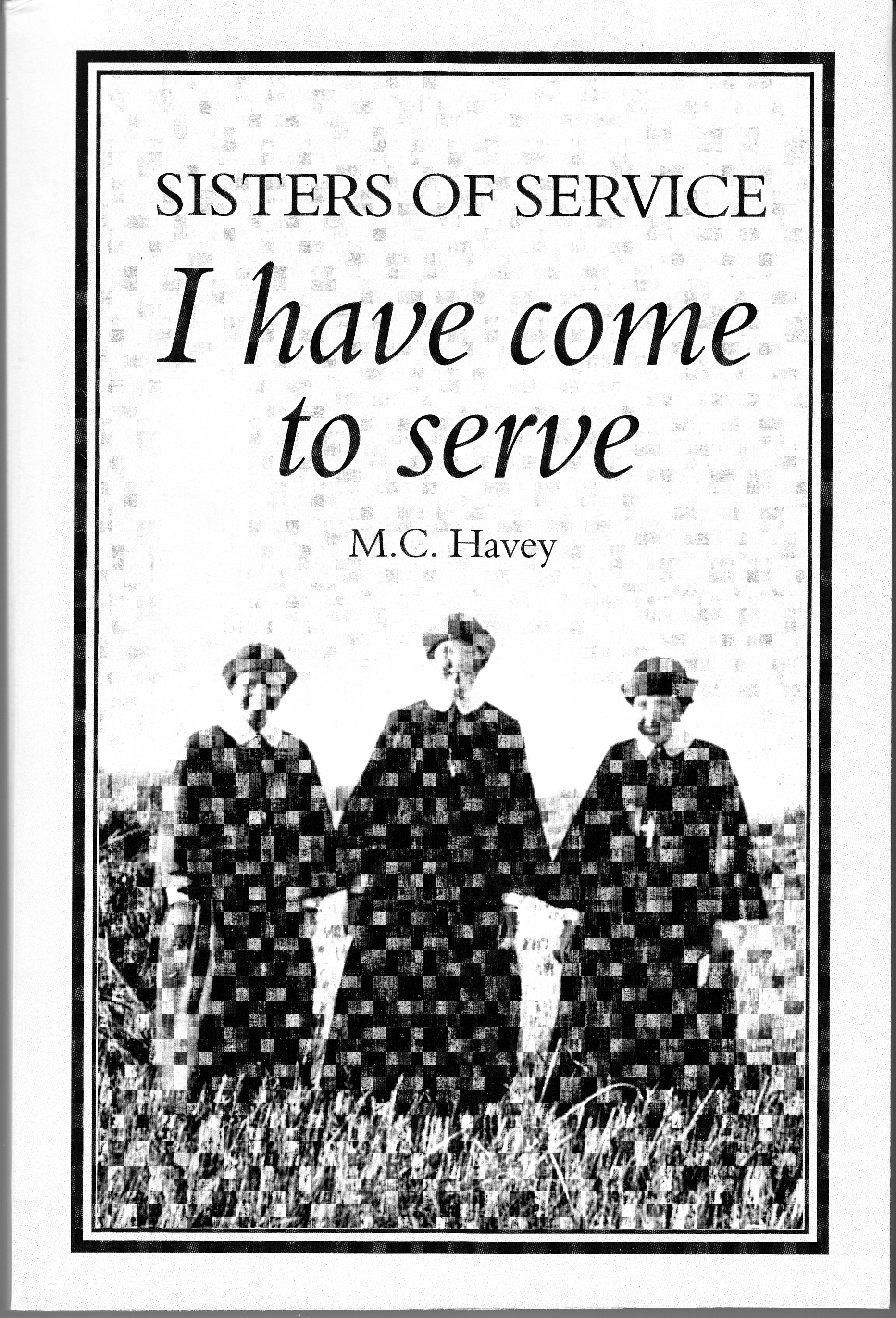

A cover of The Field at Home magazine depicting the Sisters on mission.

Under the chosen motto of “I Have Come to Serve,” the Sisters were called to be a Catholic presence among the immigrants from the ports to their homesteads as teachers, catechists, nurses and social workers among the most destitute of spiritual help in the outlying districts of the home missions. In establishing the hostels for transient women immigrants in the major cities and near the ports, the Sisters would help in the transition to Canadian life.37

In their religious work, the Sisters were to establish “catechism centers,” to provide religious instructions to children who attended public schools and to prepare them for the sacraments. In the settlements, they were to gather the people together on Sundays in the absence of the priest say the rosary, sing hymns and read the gospel. In other spiritual work, they were to instruct converts and prepare them for baptism; to take care of the chapel or churches in the district; to bring back fallen–away Catholics and to help those Catholics who were married outside the Church to have their marriage legalized in the eyes of the Church.38

In education, the Sisters were to be qualified teachers wherever they taught; take particular care of the children of immigrants; to distribute Catholic literature among the Catholics by circulating libraries in their districts. In the health field, the Sisters were to establish small hospitals; to qualify as Public Health Nurses; to provide medical care to the poor, to visit the sick at home and in the hospitals, to prepare the dying for death and mothers for birth.39

Sister Catherine Donnelly after taking her first vows at the Motherhouse, Toronto, 1924.

(SOSA 9-04.1-1-14)

On August 15, 1922, the 38-year-old Catherine Donnelly saw her vision realized: a new community of Sisters dedicated to immigrants and Western Canada was established and celebrated with a Mass in the new Motherhouse.40 From that day until after the Second Vatican Council, she became known as the first Sister of Service and the growth of the community lay in the hands of others.41

Two years later, three newly-professed Sisters were ready to embark on the first mission of Camp Morton, Manitoba. A farming and lumbering community, 60 miles north of Winnipeg, the mission was selected by Fr. Daly and Winnipeg Archbishop Alfred Sinnott because of its recent immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Chosen for the first mission were two experienced teachers: Sisters Catherine Donnelly and Margaret Guest, and a nurse, Sister Catherine Wymbs, who had been decorated by the French government for her service during the First World War. Shortly afterwards, Sister Mary Ann Bridget Burke, the second Sister of Service, joined the mission as housekeeper.42

Like St. Alphonsus living among the hill people of Scala, the Sisters of Service lived among the people in their more than 50 missions during the next 80 years. Like the Redemptorist foundations in Western Canada, the missions were small. In the cities, the SOS houses followed the Redemptorist example, and were located in the inner cities. In their parishes, the Redemptorists combined the practice of religion with social events, including concerts, plays and sports teams.43 The Sisters reflected this custom in their seven women’s hostels across Canada. The hostels served as an avenue to assist in the integration to Canada as well as social and spiritual support. The Sisters led bible study groups, Sodalities and the May coronation processions in honour of Our Lady. They also organized plays, concerts, dances, teas, bridal showers, wedding breakfasts as well as baseball and bowling teams. The hostels also provided classes in English and in various household sciences since many of the early women immigrants were seeking jobs as domestic servants. In their teaching missions in small communities, the Sisters led many extracurricular activities, such clubs as 4-H, drama, music as well as sports from track to hockey.44

On Fr. Daly’s office wall on the second-floor of the Motherhouse was a large framed motto: “Look at the Big Maps.” In these early years, Fr. Daly strove to implement a broader vision through the ideals of the Rule. In the first 15 years the Sisters not only taught in rural public schools, but were also operating a Motherhouse and a Novitiate in Toronto as well as two hospitals in rural Alberta, two religious correspondence schools and seven women’s hostels. Mindful of the Redemptorists foundations, three of the Western Canadian hostels for immigrant women were located in the same cities of Winnipeg, Edmonton and Vancouver as Redemptorist parishes.

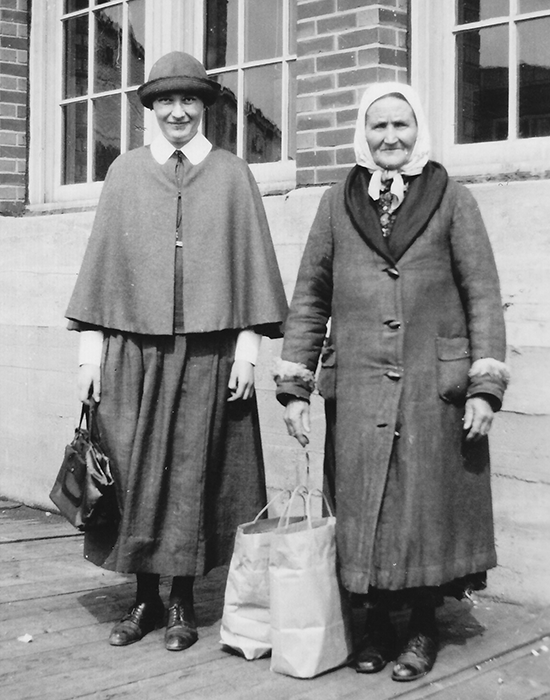

Sister Josephine Dulaska with an Eastern European woman outside the Immigration Building, Halifax, 1936. (SOSA 9-06.17.3-25-6, The Field at Home-October 1937)

In 1925, the women’s hostel in Halifax was acquired through a donation and thus in 1926 began 40 years of welcoming immigrants at the three eastern ports of Halifax, Québec City and Montréal. The Sisters’ tireless efforts in Halifax, the main eastern gateway for immigrants to Canada, now known as Pier 21, are documented on large display panels at the national historic site in that city. Following the departure of the immigrant trains from the ports, the Sisters sent names and addresses to chancery offices and parishes of the immigrants’ destinations. Sisters also assisted in locating family or relatives in Canada as well as mailing letters to announce safe arrivals in Canada.45

In 1930 during the six months when the Québec City port was open from spring to late fall, two Sisters met 184 ships and welcomed 10,724 Catholics among the third-class passengers. The Sisters distributed medals, prayer books, holy pictures and rosaries, visited the hospitals, detention quarters as well as arranging marriages and funerals.46

Sister Mary Szostak with Sudetan immigrants outside the Immigration building in Montreal, 1939.

(SOSA 9-06.17.3-27-6, The Field at Home-July 1939)

Children reading their mail at rural mailbox, 1947. (SOSA 9-02.1-18-1, The Field at Home-July 1947)

The arrival of the Sudeten refugees in 1939 illustrated the Sisters’ system of assisting immigrants to Canada as well as the interconnection with the Redemptorists. The Sisters in Montréal welcomed the Sudeten refugees, who had left Sudetenland in Czechoslavakia when it was transferred to Germany under the Munich Agreement in September 1938. After receiving the lists of immigrants’ names on the special train coaches, the Sisters provided the Sudetens with clothing before the train travelled to Western Canada. In Edmonton, the Sisters also welcomed the Sudetens and notified the Redemptorists, who were serving at the journey’s end in the northwest Alberta area of Peace River.47 In the following summers, the Sisters conducted two-week religious vacation schools for the children, who were instructed in their faith, prepared for the sacraments and the visit by the Bishop.48 In another joint collaboration, the Sisters assisted for the first two years when the Redemptorists established Settlement House in 1930 for newly-arrived German immigrants to Toronto. Two Sisters visited homes, taught English and singing, and helped with the sewing, cooking and kindergarten.49

Within four years of the community’s founding, a Canadian religious correspondence school or catechism centre was established in Edmonton, located across the street from the Redemptorist parish of St. Alphonsus. This catechism by mail was adapted from Monsignor Victor Day’s correspondence school in Helena, Montana.50

Eight years later, a similar school was set up in Regina and a third school was founded in Fargo, ND in 1939. In the first report of the Regina school in 1935, 12,101 lessons were corrected; 937 personal letters and 2,364 circular letters of information were mailed and 234 magazines were redistributed.51

In the winter months, the children in isolated rural areas would receive the lessons and the corrections by the Sisters at the correspondence school. Often little notes would be exchanged between the Sisters and their students. In the summer months at the religious vacation schools, the Sisters would meet many of the students and their families, further cementing their connection.52 Just as with the Sudetens, the Sisters prepared the children for First Communion and Confirmation. The missionary zeal clearly was apparent in these summer catechetical tours, beginning in 1925 and continued until the late 1960s. Every available Sister was assigned to religious vacation schools as the Sisters travelled in pairs to small communities at the request of the dioceses. During those years, the Sisters also instructed students in the Western Canadian Redemptorist parishes at Athabasca, Edson, Grande Prairie in Alberta; Williams Lake and Dawson Creek in British Columbia and Yorkton and Moose Jaw in Saskatchewan.53

Sister Kathleen Schenck is behind the wheel of the catechectical van with Sister Margaret Guest outside the Motherhouse, Toronto, 1931.

(SOSA 9-02.1-14-1)

Through donations, Fr. Daly acquired two catechetical vans, which the Sisters drove and lived in during their catechetical tours. Sister Margaret Murphy, then 21, recalled the drive in 1932 through the mountainous interior of British Columbia:

“Will I ever forget the swaying of the van negotiating the hairpin curves. Sister instructed me well: ‘Pray the rosary, and don’t you ever scream!’ When we began to roll backwards on a curved hill, my only reaction was a fervent ‘St. Christopher, do your stuff.’“54

In 1935, Sister Alice Walsh wrote of the six weeks of roughing it in the Redemptorist missions around Yorkton with large charts, project books and teaching supplies:

“Six weeks of talking and laughing and singing with children we have learned to know and love through the Correspondence classes, six weeks of golden summery days, of long buggy rides across the prairie, of sweet clover perfumed air, and of new surroundings, new people, new customs. Teaching Christian Doctrine is as much as part of our daily existence as is breathing in the ozone-freighted air.”55

Sister Catherine Donnelly with the congregation after Mass, Big Bar Creek, BC, 1934. (SOSA 9-02.4-4-1)

In the summers of 1934 and 1936, Sisters Catherine Donnelly and Irene Faye toured the Cariboo district of the interior of British Columbia. Sr. Donnelly relished the adventure of a missionary in the wilderness, sleeping in the car or a makeshift camp and meeting and assisting the pioneer families.56 The teaching missions, the other heart of Sr. Catherine Donnelly’s dream, expanded to 21 by the time of the community’s golden jubilee in 1972.

From the period of 1936 to 1942, Fr. Daly was appointed as consultor for the Toronto Province, holding a unique position in both the Redemptorists and Sisters of Service. During his term, six Redemptorist foundations in remote areas of Western Canada were established: Dawson Creek (1936), Williams Lake (1938); Nelson (1939), Wells (1941) in British Columbia and Athabasca (1940) and Claresholm (1941) in Alberta.57

Through all of Sisters’ hardships in their remote missions, Fr. Daly underlined Redemptorist spirituality in their mission work. Sr. Alice Walsh recalled his conference to the novices in 1927.

“Father Daly’s first concern was, of course, our spiritual development. … He pictured for us the thousands of people in areas remote from the Church, in need of our spiritual help. We were on fire to be out and doing. But with the appeal came the warning: ‘Weaklings will not stand the test of the missions. Your contact will be fruitful just inasmuch as you are in habitual contact with our Divine Saviour, no more, no less.’”58

He wrote regular circular letters to the Sisters from 1922 until 1956. In these letters, he repeatedly encouraged the Sisters to pursue their missionary zeal for the most abandoned souls in their missions. Fr. Daly also sent to each mission writings by St. Alphonsus on various subjects of incarnation, the passion, prayer, charity and humility.59

In her personal notebook of spiritual reflections, Sister Beatrice DeMarsh retyped devotional prayers to Mother of Perpetual Help and St. Alphonsus’ Method of Making a Mediation.60

Much of the Redemptorist spirituality was explained, explored and emphasized in the more than 60 retreats given by Redemptorists to the Sisters between 1922 and 1959.61 During an early retreat in 1925, Fr. Peter O’Hare quotes St. Alphonsus: “A religious who does not strive to save her soul as a saint, runs a great risk of losing it.”62

Father Peter O'Hare, C.Ss.R., with Sisters to whom he was giving a retreat, Edson, June 1939. Sister Margaret O'Hare stands behind her uncle, Father O'Hare, on his immediate right. (SOSA 9-06.10.1-28-4)

The Redemptorist influence was visible and pronounced in the number of vocations from direct or indirect contact. Of the 125 Sisters of Service, approximately 25 per cent or 32 Sisters attributed the development of their vocation directly to the Redemptorists. Of those 32, twenty Sisters came from Redemptorist parishes. Fifteen of the 20 Sisters grew up in the Redemptorist strongholds of St. Peter’s Parish in Saint John and St. Ann’s Parish in Montreal. Seven of the 32 Sisters were related to Redemptorists. Fr. O’Hare, the retreat master, was uncle to Sister Margaret O’Hare. When she received her habit in 1926, he blessed the habit and celebrated the Mass. Sr. Anne Johnson was sister to Fr. Bernard Johnson, the first Provincial Superior of the Edmonton Province, and cousin to Frs. Kleinnart and Clair Johnson of the Toronto Province. The remaining eight of the 32 became aware of the Sisters of Service and their missionary work from parish missions, retreats or talks given by Redemptorists.63

Like Fr. O’Hare, Redemptorists also presided at SOS ceremonies. Senior members of the Toronto Redemptorists served on a canonical panel examining Sisters for final profession and presiding at the profession ceremonies in Toronto.64

Administratively, the Sisters were governed in a similar manner as the Redemptorists with a Sister General and three councillors, initially for a five-year term and later a six-year term.65 Once during a council’s term, an extraordinary visitor in the place of Sister General would conduct the annual visits to each mission, similar to the custom of the Redemptorists with the visitors from Rome.66

In 1937, the administration of the Sisters of Service changed when the Chapter delegates elected the Sister General and the Council.67 Previously, the administration had been appointed by the Toronto Archbishop on the advice of Fr. Daly.68 This change also coincided with the start of Fr. Daly’s term as consultor for the Toronto Province.

Fr. George Daly on his annual visit outside the Camp Morton residence, 1945. (SOSA 9-06.4-3-54)

Father John Lockwood, C.Ss.R., Provincial Superior of the Redemptorists' Toronto Province, presides at the profession of vows in the Motherhouse chapel, Toronto, 1965. (SOSA 9-05.2-84-3, The Field at Home-October 1965)

During the next decade, a gradual shift occurred with the Sisters’ elected council increasingly assuming more of the administrative duties. After the Chapter of 1948, Fr. Daly, then 76, relinquished most of his responsibilities.69 However, he continued yearly visits to the missions and encouraged the connection with the Redemptorists.

In 1948 when the Redemptoristines arrived in Toronto, the Sisters assisted them in establishing a monastery. When Superior General Leonard Buys visited the Sisters of Service Novitiate in 1951, the Redemptoristines joined him and a family portrait was taken.70

By the time of Fr. Daly’s death in June 1956, the Sisters of Service were debt-free71 and had established 32 missions, which fulfilled all the components of the Rule. His death and changes in both communities following the Second Vatican Council resulted in less contact than in former years.

Toronto Provincial Superiors still presided at profession ceremonies and confreres led retreats, celebrated Masses for jubilees, funerals and Chapters. As the Redemptorist membership declined, celebrants were drawn from other congregations.

However, changes following the Second Vatican Council also saw the Sisters and the Redemptorists serving on parallel ministries in Brazil during 1969 to 1971.72 In examining their charism after the Second Vatican Council, the Sisters were assisted by a survey conducted by Fr. Edward Boyce,73 later the first elected Provincial Superior of the Toronto Province in 1968.

Since 1965, the Sisters have continued the broader vision to serve “the most in need” as parish workers and religious education co-ordinators in eight Canadian parishes, including the Redemptorist parish in Edson, Alberta. The Sisters have welcomed the new wave of immigrants, with spiritual support and English classes. In 10 missions, the Sisters have served Canada’s natives peoples as teachers and social workers living in trailer homes or apartments. Instead of the two hospitals, SOS nurses were employed in seven public health positions located from the Canadian Arctic to remote northern communities, where the Church is not present.74

Following the Second Vatican Council, the community collaborated with the National Office of Religious Education in Ottawa to develop home catechetical programs to enrich the faith of families and children as well as to assist teachers and catechists to update teaching methods.75

Continuing to be pioneers in mission, the Sisters in 2003 established the Catherine Donnelly Foundation, a registered non-profit charitable organization, to honour the memory and extend the mission of their foundress. Partners with the wider community across Canada, the Sisters through the foundation remain promoters of positive social change and in the spirit of St. Alphonsus “to serve the most in need.”

Sisters of Service I have come to serve is an illustrated history, published in 2022 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the founding.